On rawdogging David Foster Wallace

The Pale King is a long, dense argument in favour of reading long, dense books

“Television is the way it is,” David Foster Wallace wrote in 1993, “simply because people tend to be really similar in their vulgar and prurient and stupid interests and wildly different in their refined and moral and intelligent interests.”

I like that quotation because beneath the surface are swimming all the cultural demons with whom Wallace liked to dance and spar. Wallace for the most part wrote about two subjects, really: difficulty and boredom. In fact, I suppose there’s actually also a third theme, which is the interrelation of the two. Call it willpower: how it’s important to be bored sometimes, to achieve difficult things, and that easy things are rarely worthwhile. Stupid things are usually easy and refined things are often hard.

Television, for Wallace, was the epitome of that dilemma. It was, in early 1990s America, the easiest form of entertainment you could choose to consume, and probably the stupidest – stupider than hair metal, stupider than The Far Side, stupider than Dan Quayle (okay – perhaps not quite as stupid as Dan Quayle). Even so, Wallace himself enjoyed watching TV, and was fascinated by it. He allegedly watched Beethoven on VHS over and over again in the background while editing Infinite Jest, itself a novel about a killer video tape – more on that later. Yet Wallace also despaired, publicly, over what he thought it was doing to the American mind.1

I recently finished reading Wallace’s unfinished novel The Pale King, which was published posthumously in 2011. It’s a fragmentary book which follows the various scattergun experiences and inner lives of a dozen or so named characters who work at the Inland Revenue Service in Peoria, Illinois in 1985. Suffice to say, while the novel is charming, funny and entertaining, the lives of these characters as described by Wallace are decidedly not. On the surface, they are insanely boring and mundane, characterised by petty insecurities and psychosexual hang-ups and inhabiting deeply unsexy places – but the unsung service they provide by examining tax returns, debating minor points of efficiency within the IRS and the byzantine tax code of the USA, quoting subsections of tax law to each other while jostling for positions in the Service’s hierarchy… all of this is painted by Wallace as a noble calling.

Tax accountancy, per The Pale King, is the opposite of watching TV: it’s infinitely more difficult, complex and boring, and also an infinitely more important and worthwhile use of one’s time.

And so the book got me thinking about that whole antagonism between the easy – the “vulgar and prurient and stupid interests” – and the difficult – the “refined and moral and intelligent”. There’s a debate going on at the moment in the media about perceived parallel, linked crises of literacy and attention span, all of which are further entangled with questions about snobbery and elitism and poptimism and the value of art. And this stuff is important. If politics and economics are the big slabs of stone laid in the foundations of civilization, then culture and art are surely the cement that sticks them together. This stuff – the cement – matters.

Writing about Wallace on Substack is the literary equivalent of chumming the water. (Like an idiot, it was only after I had written 4,000 words of this piece that I found Patricia Lockwood, of all people, had turned her polemical disruptor beam on DFW over 8,000 words in the London Review of Books; just my luck.) Oh well. Everyone has a take. This is mine.

i. The Poptimist Turn

To understand why something like The Pale King matters, you have to first understand poptimism. Poptimism is the idea, broadly and innocently conceived by the music critic Kelefa Sanneh in the early 2000s, that rock music was taken seriously by music critics at the time, while pop music wasn’t. These fellow critics of his, Sanneh wrote, might be called “rockists”, and they were, ultimately, haters and gatekeepers who “reduced rock ‘n’ roll to a caricature”, and then used that caricature “as a weapon”. They were the old guard, the self-regarding fogeys and nostalgia merchants who sneered at the new and worshipped greying snake-hipped pensioners and those who slavishly imitated them.

It might be better to quote Sanneh directly, writing in the New York Times in 2004:

Rockism means idolizing the authentic old legend (or underground hero) while mocking the latest pop star; lionizing punk while barely tolerating disco; loving the live show and hating the music video; extolling the growling performer while hating the lip-syncher.

Over the past decades, these tendencies have congealed into an ugly sort of common sense. Rock bands record classic albums, while pop stars create ‘guilty pleasure’ singles. It’s supposed to be self-evident: U2’s entire oeuvre deserves respectful consideration, while a spookily seductive song by an R&B singer named Tweet can only be, in the smug words of a recent VH1 special, ‘awesomely bad.’

Why? To Sanneh, there was no reason to distinguish between the likes of Bono and the Edge, and Tweet.2 Taste was subjective. If art was fun, it was good. “Are you really pondering the phony distinction between ‘great art’ and a ‘guilty pleasure’ when you’re humming along to the radio?” he asked.

What was worse, the rockist stance could be indicative of worse impulses: Sanneh (correctly, in my view) pointed out that this dichotomy of “serious” rock and “unserious” other genres was informed by (often unintentional) homophobia, sexism and racism. Preferring rock music made by white guys to implicitly gay disco, girly R’n’B or black hip-hop could be a sign of unconscious prejudice. It was, he implied, time to break the hold guitar bands had over criticism for the good of music – and for society at large.

This would require a new movement. Sanneh didn’t name it, but it became chirpily known as “poptimism” nonetheless. His New York Times piece was the first stone thrown at the protest; Sanneh was the first poptimist apostle, metaphorically setting himself on fire before the gates of the Rolling Stone’s Ministry of Truth.3

Well. How times have changed.

In 2025, critics at serious newspapers, magazines and other outlets fall over themselves in their attempts to prove they are good poptimists. The poptimist turn has gone beyond music and is now the water in which all cultural criticism swims. Poptimism applies to everything. It is the default setting on which to talk about art. But its definitions have become bloated and its scale obscene.

Here’s my take: despite Sanneh’s intentions (as far as I can tell), poptimism was part of a wider trend which broke down any kind of social judgment associated with taste. The admirable initial aim was to have pop music considered by critics on an even footing with rock music. No longer would it be a “guilty pleasure”, as he noted in the New York Times. But instead, what happened was that some people used the guise of poptimism – the arguments it birthed – as permission to stop challenging themselves in any significant way. Any art which required investing time to understand was thrown out into the cold; anything that was a bit complex was regarded as the purview of snobs and pseuds. People were given permission to consume only their guilty pleasures – because suddenly the idea of a “guilty pleasure” itself was anathema.

Obviously, the market followed the trend. So, regrettably, did politics. This attitude spread from music into the arts more generally, and then out further into society itself. Why ask students at Yale to read Leviathan and then discuss it when they can just listen to Lover instead? Why bother, as you move from teenagehood to adulthood, to leave the MCU behind? Whether in pop culture or in life, it was easier to do something easy – to consume something easy – and then make up a principle to justify it afterwards: it’s progressive to steal from your favourite artists, actually. Mental health means I can cancel on my friends last-minute, and it’s ableist to suggest otherwise. Charli XCX’s endorsement of Kamala Harris matters and you’re out of touch if you find it embarrassing.

In this world, accessibility and simplicity became the only qualities that really mattered in pop culture. Kids stopped dabbling in the seductive signifiers of adulthood: having sex, taking drugs, drinking. The avant-garde died a quick death and was barely mourned. Interest in pushing mass art, so tightly woven into the DNA of the modernist moment of the long 20th century, waned away.

Where was the future?

Mark Fisher, the late British academic and self-described “hauntologist”, wrote extensively about this phenomenon. It was something he called “the slow cancellation of the future”. “The ‘futuristic’ in music,” he wrote, “has long since ceased to refer to any future that we expect to be different; it has become an established style, much like a particular typographical font.” Fisher thought that Kraftwerk were one of the last artists who might have been considered truly futuristic when they started making and releasing music in the 1970s. “Where,” he asked, “is the 21st-century equivalent of Kraftwerk?” It sure as hell isn’t Wicked.

Liking stuff that was once considered childish, uncool or overly simplistic isn’t a bad thing any more. Living a life in a way that once would have been embarrassing no longer was. Easy is in, difficult is out.

Freddie DeBoer summarised this recently with typical verve:

It turns out that, when you change social norms to give people permission to never stretch themselves in terms of consumption (of music, of movies, of food), very many will just default to consuming the easiest, safest, and most comfortable product out there. You could argue that this means that pure cultural populism is inevitable because that’s what people really like, so let’s shut down all the black box theaters and arthouse cinemas and alternative music venues. Or you could argue that, since it’s good for people to expand their cultural palates and be exposed to new and challenging things that they might not ordinarily try, it’s essential that we have a shared social expectation among adults that our tastes should evolve and grow over time. Can’t see that one ever coming back, though. People want to live their whole lives in emotional sweatpants.

But you know that eating shit will make your body go soft and ugly. You don’t think people who go to the gym are snobs. So why accept the same for your mind?

ii. The Chattering Cyclops

So, back to Wallace, who cared a lot about this idea, and anticipated it by about 20 years. He famously outlined it when delivering his “This is Water” commencement speech at Kenyon College in Ohio in 2005. If you’ve only read one thing by Wallace, it’s likely to be this speech. If you haven’t, well, let me quote it again (emphasis my own):

Twenty years after my own graduation, I have come gradually to understand that the liberal arts cliché about teaching you how to think is actually shorthand for a much deeper, more serious idea: learning how to think really means learning how to exercise some control over how and what you think. It means being conscious and aware enough to choose what you pay attention to and to choose how you construct meaning from experience. Because if you cannot exercise this kind of choice in adult life, you will be totally hosed. Think of the old cliché about “the mind being an excellent servant but a terrible master.”

[…]

And I submit that this is what the real, no-bullshit value of your liberal arts education is supposed to be about: how to keep from going through your comfortable, prosperous, respectable adult life dead, unconscious, a slave to your head and to your natural default setting of being uniquely, completely, imperially alone day in and day out. That may sound like hyperbole, or abstract nonsense. Let’s get concrete. The plain fact is that you graduating seniors do not yet have any clue what “day in day out” really means. There happen to be whole, large parts of adult American life that nobody talks about in commencement speeches. One such part involves boredom, routine and petty frustration. The parents and older folks here will know all too well what I’m talking about.

He goes on to outline the humdrum life of someone who sounds very much like a character from The Pale King – an eight-hour white-collar day in a mind-numbing office, followed by a frustrating and alienating trip to the spiritual wasteland that is the local supermarket, “hideously lit and infused with soul-killing muzak or corporate pop”. It is, Wallace suggests, somewhat heroic to make it through this sort of experience without despairing. It’s a sign of maturity.

It’s no coincidence that Wallace achieved fame as a writer in the 1990s, and that he was interested in boredom and frustration. It was very 90s to be bored, after all – that’s essentially what two of my favourite slacker-adjacent films, Clerks and Office Space, are about (Jill Sprecher’s Clockwatchers is a fellow traveller). Combine boredom with the booming material prosperity of the 1990s and the self-awareness that was dawning – late – about the corporate, depersonalising spirit of the 1980s workplace, and you have this great recipe for ennui (see also: The Matrix, Fight Club, American Beauty, basically any film released in 1999). Wallace may have written The Pale King in the early 2000s, and it may be set in the 1980s, but his sensibilities and those of the novel are still those of Gen X: they are deeply and irrevocably rooted in the last decade of the millennium.

The 1990s was also a decade when people were obsessed with TV, and with debating its potential brain-numbing effects. In “Sideshow Bob’s Last Gleaming”, an episode in season seven of The Simpsons which first aired in November 1995, Sideshow Bob holds Springfield hostage, threatening to detonate a nuclear bomb in the city unless its populace bans television. He fails, of course, with typically poetic élan – “How naïve of me to think an atom bomb could fell the chattering cyclops!” he emotes dramatically – but it’s hard to watch the episode now and not consider its parallels with the debate around TikTok and other infinite-scroll attention vortices. Our ability to concentrate, to suffer boredom, to find satisfaction in difficulty – it’s been shot to shit.

The Pale King is about all of these things.

iii. The Entertainment

I’m acutely aware that relatively little of this is a good advertisement for why you should read all 573 pages of The Pale King. Let me try to sell it a little better.

The eagle-eyed among you will have noticed that this book was published in April 2011, three years after Wallace’s suicide. It is unfinished, but Wallace left a huge volume of notes and drafts organised in his office before hanging himself; one wonders the extent to which it crossed his mind that something might be put together from them when he was gone. Whatever the case, it was – put together, that is – by his longtime editor Michael Pietsch, into whatever narrative form could be gleaned from the notes Wallace left (a swathe of the material that couldn’t quite fit now makes up the appendices to the book). Pietsch had long heard rumours from Wallace’s agent Bonnie Nadell before his death that he had been working on a second novel about the IRS. “If anyone could make taxes interesting,” Pietsch writes in the introduction to The Pale King, “I figured, it was him.” Pietsch was correct.

From the get-go, The Pale King wears its quiet themes loudly. The opening scene follows a mid-level IRS employee named Claude Sylvanshine on a small aeroplane flying over the Midwest. Sylvanshine is preparing for an accountancy exam he has to take if he’s to be eligible for a promotion, and he is also a nervous flyer. He has a trapped nerve in his neck and upper back which is aggravating him. To take his mind off the bumpy flight and the pain in his neck, he runs through formulae and accountancy laws, over and over again, reciting them to himself as though they were spells, charms or wards against danger and discomfort. “It was true,” Sylvanshine thinks to himself as he tries to keep himself from visualising a plane crash. “The entire ball game, in terms of both the exam and life, was what you gave attention to vs. what you willed yourself to not.”

The sentences in The Pale King are long. The type is tiny. Here’s a sample, from a sort of self-imposed Proustian recollection Sylvanshine has during his flight, of a doomed date he once went on:

Sylvanshine had once been on a first date with a Xerox rep who had complex and slightly repulsive patterns of callus on her fingers from playing the banjo semi-professionally as her off-time passion; and he remembered, as the overhead bell again rang and the sign lit, the no-cigarette glyph legally redundant, the pads’ calluses deep yellow in the low dinnerlight as he’d spoken to the musician about forensic accounting’s intricacies and the hivelike organization of the Northeast REC, which was only one small part of the Service, and the Service’s history and little-understood ideals and sense of mission and the old joke (to him) about how Service employees in social situations would go to such absurd lengths to avoid telling people that they worked for the IRS because it cast such a social pall because of popular perceptions of the Service and its employees, all the while watching the calluses as the woman worked her knife and fork, and that he’d been so nervous and tense that he’d yammered on and on about himself and never asked her sufficiently about herself, her history with the banjo and what it meant to her, which was why she hadn’t liked him enough and they hadn’t connected. He’d never given the woman with the banjo a chance, he saw now.

That first one’s a 204-word sentence; most writing classes would tell you to keep them to less than ten.

And yet Wallace on concentration is a sort of metafiction; his writing is dense and hard to parse because he is not only writing about how it can be hard to concentrate, but he wants you to feel it as you read him. So it’s important to realise his books embrace boredom and difficulty, and play with them. They make you work for their jokes (which, you might be surprised to learn, there are in abundance)4, and they kind of mock you gently. The thousand-page Infinite Jest is all about something called the Entertainment – a McGuffin VHS tape which is so addictive and compelling it kills people, who simply watch it over and over again until they starve. Literal death by TV!

In Wallace, the form of the text itself is as much the point he’s making; he makes his writing dense and complex and seemingly impenetrable so that you get the gist even further as to what he is saying about density and complexity and impenetrability – and how working through them can be more satisfying than instant gratification. (Wallace’s mum was an English professor and his dad taught Philosophy. It’s not a surprise he had a penchant for very, very long sentences.)

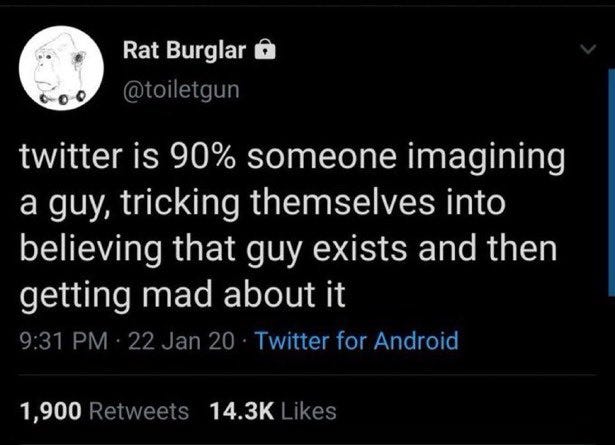

Ironically, people who like Wallace’s writing seem to get this (perhaps they are flattered by the implication that they are somehow smarter than others for being able to plough through the text); people who do not like it do not (get it). This is a phenomenon I see a lot in the discourse around him. People like to dismiss Wallace as pretentious, so much so that he has become a byword for that guy at parties who bores girls by talking about Infinite Jest (please note: that guy does not really exist). And yet almost never have I come across anyone who has deployed Infinite Jest as a punchline who has actually read or even attempted to read it.5

In The Pale King, Wallace takes this metafiction – the idea that the book should resemble, in aesthetic form on the page, its own central idea – a step further. Large swathes of the book are narrated by a fictionalised version of “David Wallace” himself, recounting a (fictional) period in his early 20s in which he worked for the IRS in Peoria. Wallace, the in-the-flesh man, did not do this, but he and Wallace, the character, converge in voice – it is very obviously him who is speaking in the book, particularly when he recounts learning, during that period, how to concentrate on tax returns for a serious and extended period of time.6 The first time he does it, he literally begins the chapter “Author here. Meaning the real author, the living human holding the pencil, not some abstract narrative persona.”

Except, of course, it is a constructed narrative persona; the whole section provides a sort of retroactive origin story, which explains not only The Pale King, but also Infinite Jest and, well, Wallace’s entire self-consciously overwrought style, but it also drives home the fact that Wallace wants you to apply the (in air quotes) “lessons” of this book beyond its covers. It’s a novel with points to make. It’s about how he himself learned not to fear boredom.

iv. The mystical power of boredom

You might remember that last summer there was a brief fashion for – Lord forgive me the phrase – “rawdogging” long plane flights. People, mostly young men, would brag about sitting on two-, three-, seven-, fifteen-hour flights without falling asleep nor consuming any media or entertainment throughout. The rule was that you had to look at the flight map alone, and in some hardcore instances, you weren’t even allowed to do that. You just had to sit there and wait for the flight to finish.

Why?

I suppose that that a first “point” in The Pale King might be that learning to deal with boredom can be a blessing. We’re so rarely bored, these days, but we’re also always bored. Like many of Wallace’s aphorisms and the bits of wisdom he imparts like those in This Is Water, that sounds obvious and trite, but it’s true. You can be bored and entertained at once – scrolling your phone being the best example of this. When, as outlined above, the culture is too easy, it also becomes boring.

Says Wallace, “in character” as himself in the book, looking back on his (fictional) time as an accountancy student:

To me, in retrospect, the really interesting question is why dullness proves to be such a powerful impediment to attention. Why we recoil from the dull. Maybe it’s because dullness is intrinsically painful; maybe that’s where phrases like ‘deadly dull’ or ‘excruciatingly dull’ come from. But there might be more to it. Maybe dullness is associated with psychic pain because something that’s dull or opaque fails to provide enough stimulation to distract people from some other, deeper type of pain that is always there, if only in an ambient low-level way, and which most of us spend nearly all our time and energy trying to distract ourselves from feeling.

I think this is a correct supposition. I think that that “psychic pain” is what you feel when you wake up on a sunny Saturday, hungover, and start playing video games, then look up and realise eight hours have passed and you haven’t left the house. Somewhere in the back of your mind you know that your life is slipping away, day by day, and you’re wasting it by taking the easy option.

By contrast, later on, a professor tells Wallace that “Enduring tedium over real time in a confined space is what real courage is.” I think that, in its own troglodyte way, the rawdogging trend tapped into something like that. It was a way to take on dullness – to fight it, beat it, and prove you weren’t afraid of psychic pain (though there was a certain fallacious irony to posting about it so much on social media, of course).

Not only is boredom a blessing, though – the ability to concentrate through it is literally a magical power in The Pale King. By which I mean, people who can concentrate hard enough display sub- or unconscious supernatural abilities in the book.

Wallace always liked ghosts – Infinite Jest was of course based on Hamlet (to refresh your memory, the title is from the “Alas, poor Yorick” soliloquy and the novel’s first two words, “I am”, consciously and famously answer the first two of the play: “Who’s there?”).7 In that book, the protagonist Hal Incandenza’s father, a filmmaker who directed the eponymous killer video, a.k.a. the “Entertainment”, appears to haunt the tennis academy at which Hal lives and trains, as the late King Hamlet does Elsinore.

Well, anyway, there are two ghosts in The Pale King which haunt the IRS facility, and one of its employees also seems to have ESP. (In fact, it’s Claude Sylvanshine, the gabardined man from the bumpy flight mentioned above.) He has uncontrollable, momentary visions, not of the future, but of “ephemeral, useless, undramatic” data sets pertaining to the people he encounters around him. He is a “fact psychic” who will become aware at random of facts: the middle name of the childhood friend of a passing stranger in a corridor; the number of blades of grass on the front lawn of his postman’s home; “the length and average circumference of Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger’s small intestine”.

And then there’s Shane Drinion, who can levitate several centimetres off his chair, unwittingly (he literally does not notice), when entering a state of pure concentration.8 Drinion gets one of the book’s longer and more moving single scenes, about 60 pages long and set in a bar at a post-work drinks, where another tax examiner called Meredith Rand is explaining in depth how she met her husband while committed to a mental hospital for self-harm. Rand is “wrist-bitingly attractive”; Drinion has something akin to a super-high-functioning autism. Throughout, Rand is trying to tell whether Drinion is listening to her only because she’s beautiful, pretending not to notice she’s beautiful, or not listening to her at all – all of which options she hates, for reasons that become clear as she tells her own story to him – but actually, it seems that the asexual Drinion is just really, really good at concentrating. And, as he becomes more and more rapt in her story, asking the occasional question but mostly just listening, he begins to float off his chair. Very slightly. Rand herself doesn’t consciously notice, but he levitates:

It’s either her imagination or Drinion is sitting up steadily straighter and taller, because he seems to be slightly taller than when the tête-à-tête started. A collection of different kinds of old-fashioned fedoras and homburgs and various business hats glued or pinned somehow to a varnished rosewood board that had been visible on the opposite wall of Meibeyer’s over Drinion’s head is now partly obscured by the crown of his head and the slight cowlick that sticks up at his round head’s apex. Drinion actually is levitating slightly, which is what happens when he is completely immersed; it’s very slight, and no one can see that his bottom is floating slightly above the seat of the chair.

And but so concentration is quite literally a magical ability in The Pale King.

v. Bliss in every atom

There is a final ghost in the book. It is the ghost of the book that Wallace didn’t finish. I don’t know how long The Pale King would have been in its final form. Infinite Jest is 1,079 pages long, including its footnotes, which all come at the end, while The Pale King is 540, coincidentally almost perfectly half. It is, however, then followed by 33 pages of draft notes by the author that his editor decided to include that give hints as to how the novel might have played out.

There are several of these which make you almost ache, having finished reading the book, for its impossible Wallace-approved final edit. One of these is the suggestion that the platonic Drinion-Rand relationship would have deepened – I wish I could have read this in particular. There are hints and parallels with Infinite Jest that were never explored fully: Rand, that “wrist-bitingly attractive”9 tax examiner vs Infinite Jest’s “P.G.O.A.T.” – prettiest girl of all time – Joelle van Dyne, who is forced to wear a veil to avoid the unwanted attentions of men but who may also be hideously disfigured; Rand, the teenage cutter vs the institutionalised, anhedonic Kate Gompert; fictionalised versions of Wallace in the form of Hal Incandenza, a fellow tennis prodigy, and the author-accountant Wallace in The Pale King. There are other themes that feel hugely relevant today, like generational conflict, willpower vs addiction, humans vs machines (The Pale King was meant to feature a competition between Drinion, the best human IRS examiner, and a new computer which threatens to replace all the examiners).

At risk of sounding like that guy I claimed didn’t exist earlier – the guy who tells people to read Infinite Jest at parties – I never get as much from any other author as I do Wallace. I think about his novels for a long, long time after I read them. They are complex and interlocking and they work as works of art on their own, but they are also deeply concerned with the real world. They have ethical systems attached to them; books nowadays never have ethical systems attached to them! Most of all, they can be difficult to read and understand, and thinking about them in great depth – over 5,000 words… – is something that makes me very happy. They’re not easy art.

Wallace knew that being bored, engaging in intense concentration and finding meaning in life were three facets of the same spiritual journey. That’s why Shane Drinion, of all the motley freaks and losers in The Pale King, was the most satisfied with his own life. Wallace’s notes in the appendix say as much. “Drinion is happy,” he wrote. “Ability to pay attention. It turns out that bliss – a second-by-second joy + gratitude at the gift of being alive, conscious – lies on the other side of crushing, crushing boredom.

“Pay close attention to the most tedious thing you can find (tax returns, televised golf), and, in waves, a boredom like you’ve never known will wash over you and just about kill you. Ride these out, and it’s like stepping from black and white into color. Like water after days in the desert. Constant bliss in every atom.”

And we all have American minds in 2025, whether we are American or not.

Having not heard of her before writing this piece, I looked Tweet up. Turns out she carved out a good career through the 2000s and 2010s, and her music feels like the sort of un-self-conscious thing people my age (31) are increasingly returning to listen to on big, cheesy nights out. Think Missy Elliot, Fat Joe and Ashanti, Ciara, TLC. If you’ve ever been to Rowan’s Ten Pin Bowl in Finsbury Park, you’ll know what I mean.

Though can you imagine how cool it would have been if he had literally done it in real life? Imagine hating Led Zeppelin that much.

Wallace is a nerd, so he does things like call overbearing HR officials “Richard Tate”, i.e. “Dick Tate” – dictate. Another is called, tongue-twisterly, “Merrill Errol Lehrl”. Try saying that in Wallace’s American drawl.

In more niche, literary circles you can sometimes swap in someone like Ben Lerner for this. Pynchon, Don DeLillo and Roberto Bolaño also work nicely.

Notably, these swathes by “David Wallace” are the only sections in which he shows the real-life David Wallace’s signature usage of very, very long footnotes.

In Wallace’s appendices at the back of The Pale King, included by his editor, he suggests explicitly that two characters live together and resembled Rosencrantz and Guildenstern.

There’s also a character called Chris Fogle. Wallace’s unused notes suggest that Fogle might know a secret string of numbers that if recited (or something) can cause a state of total concentration, too. The more you look at this Peoria outpost of the IRS, the more it resembles that secret wartime research facility on the South Coast, “The White Visitation”, from Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow, where a ragtag group of psychics have been assembled to try to beat Hitler. Pynchon and Wallace are often compared, though one gets the impression Wallace wouldn’t like the suggestion of a similarity.

I know I already quoted this phrase but I love it enough to put it in again.

Wallace's writing has a reputation for being dense and complex and impenetrable, but it doesn't seem that way when you're reading it. Yes, the sentences are ridiculously long, but they all make perfect sense, and they're absolutely delightful. His reputation for being intimidating gets in the way of just enjoying his work, and that's a shame.

I love the part: "You don’t think people who go to the gym are snobs. So why accept the same for your mind?" Yes, exactly. Especially in an era so rich in information, why do so many choose to feed junk food to their minds? Nothing wrong with junk food *once* *in* *a* *while* but a steady diet of it isn't healthy. Likewise, the embrace of overly simplistic pop content. Nothing wrong with it in itself, but when it's all one consumes, one becomes simplistic and without depth or nuance. (The proof of how disastrous this is for minds currently squats in the Oval Office.)

Because of "must read" recommendations, I've tried to read "Infinite Jest" three times but have never been able to stick with it. Perhaps, in part, because, when it comes to fiction, I'm all about good storytelling and don't find brilliant literary exercise engaging. For me, stories aren't about technique, they're about being transported to interesting worlds. It may also be in part because I've long seen the world — judging from your post — in much the same ways that Wallace does. My big ask for fiction is to take me someplace new, and Wallace just doesn't. Though I tend to agree with his point of view.

For example, that commencement speech. I've been ranting about what I called "The Death of a Liberal Arts Education" since the mid-1970s. I quite agree with him but was there long ago. Likewise, the notion of filling mental space to avoid facing the emptiness in oneself. Back in the early 2000s, when walking to my car after work, I noticed how many people doing the same thing were chattering on their cellphones. For me that walk was a chance to detune from the workday, and I wondered why anyone would sacrifice the peace and quiet. I decided they were afraid to be alone inside their own heads.

Good post, and I agree with every point you made. (Except for reading IJ or TPK, but that's just a taste thing. 😁)